Large Octagonal garden table

Introduction

The green plastic garden table we bought 20 odd years ago was looking a bit shabby (and saggy it has to be said), so a management order was placed for a new garden table. So the question then was, what should it look like?

I have always quite liked the look of the small octagonal table that Stan made, however I needed something that could seat up to eight - so it needed to quite a bit larger. There are plenty of small spindly looking octagonal tables on the web, but nothing really floated my boat. So I decided I wanted something a bit closer in scale to a Mouseman dining table (although without the £4k price tag)

So the ubiquitous sketchup model was cobbled together for a table approx 60" wide, and standing around 30" from the floor.

Materials

Since this is an outdoor project, we needed something fairly durable, and for one reason or another I had a number of large oak boards sat in the workshop waiting for a good project. So that decision was easy.

Construction

To avoid oak staining from contact with steel fastenings and moisture, I opted for a traditional style of mortice and tenon joinery.

The Base

So the first bit to make was the base. This was to consist of a sculpted cruciform set of feet, that would support central column. The column would then be attached to 4 radial "wings" to add some width and heft to the base. (since the design is by nature "top heavy", the base wants to be fairly heavy and the top comparatively light weight).

A couple of 2"x2" boards were glued up to make the central column. Some full length mortises were routed into the sides of this, and a decorative "stopped" bevel added to the corners:

Next job was was the "wings" that fit to the sides of the column.

These needed some tenons cut at both ends and the side, but this was easier to do while they were still rectangular. A quick run past a dado blade on the table saw doing most of the work.

Next we needed the base - this is basically a large cross shape made from two 4"x2" timbers with a half lap saddle joint in the middle. To get the foot profile I started with a sketch of the shape, and transferred this to a bit of spare laminate flooring someone had given me (the thin MDF with a melamine face is quite good for template making, and also nice and easy to work and fineness into smooth curves etc). Then I used the template to trace out the shape onto each leg, before cutting them out on the bandsaw.

The width of the feet meant that I could not use a flush trim bit in a router after, so had to cut carefully, and then do the final shaping using a spindle sander, and finally a random orbit sander with a soft interface pad fitted to get the smooth curves.

Is there a point in a project you reach "peak router"?

Is there a point in a project you reach "peak router"?

The final bit of shaping work for the base was to cut the curve into the wings, and add a small bevel to the edges. So another laminate flooring profile template was made. I used this to draw the curve before cutting close to the line on the bandsaw:

With this bit it was easy to use the template to make the final finish cuts as well.

I could copy the edge of the template to the timber. One thing I had to watch with the curve is that at some point you will find yourself cutting against the grain direction in a way that can make brittle woods like oak chip out.

The solution is to "climb cut" the tricky part of the slope (i.e. cutting in the wrong direction). Climb cuts can be dangerous, but are usually ok if you are only removing a small amount of material. The final result is nice smooth shaped profile that exactly matches the template.

Base assembly

The last bit of work on the base was the assembly. While the side wings can be glued to the central column (Titebond III since its waterproof), because there is a substantial width of cross grain timber in long "with the grain" mortices in the base, I needed a way to fix the wings to the feet in a way that would not cause problems with seasonal movement and humidity changes. So rather than glue these, I decided that allowing for some "slip" in the mortices, and dry fit them using timber pins. The holes in the tenons being suitably widened to allow for movement, and the mortice being cut a bit wider than the tenon.

Making walnut dowels

This did of course mean I needed some suitable dowels. I decided to opt for walnut since this might make a nice contrast. To make the dowel, I needed a "jig" (calling it a jig is perhaps over egging it a bit), but basically a bit of steel (in this case some fairly heavy gauge angle iron)with holes drilled in it. I could then rip a thin strip of wood off on the table saw, and knock the corners off with a plane. whittle down the ends to leave a small point on one end, and something that will go in a drill chuck on the other.

Base glue up

The first bit of base (centre column, and two wings) was a nice easy glue up. However to do the final cruciform shaped arrangement with all four wings required a slightly more complicated setup to get the clamping force in the right place:

The small clamps and the splint of wood at the end ensure everything sets up in line.

Once the central column was complete, it could be set into the feet, and the dowels driven through.

The Top

I had designed the octagonal table top as a frame, with slats that would "fill in" the middle bit. The frame would be supported by a pair of crossed "arms" that would sit on top of the base.

For this to work and look good, we needed a very well fitting ring of wood to go round the perimeter of the table. So the first trick was to make sure I could cut the angles accurately on the ring. To test this I made some test pieces out of some very thin sections of scrap pine.

The joints all looked tight enough, so time to cut the real timbers. The perimeter is made from 2.5" wide stock about 1" thick.

The next decision was to how these sections would join. To get a really strong joint I decided that cutting saddle joints into the ends of each section, would then let me use a substantial slip tenon to join them.

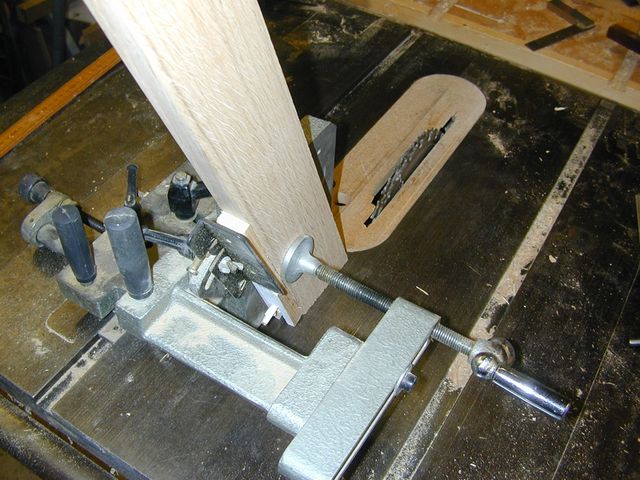

So next I cut the mortice for the tenon using a tenon jig on the table saw fitted with a dado blade:

Having done this, the tenons could be glued into place on one end of each segment:

I then made a drilling jig:

That could be used to consistently place holes through the ends of each segment and the slip tenons. More walnut dowels could be driven though the holes and planed flush to add strength to the joint and some visual appeal

Draw bore clamping

I decided that gluing and clamping up a large octagon would probably be quite tricky. So I figured I could make life much easier if I used the draw bore technique to not only pin the joints, but also pull them firmly together.

So I started by drilling more holes with the guide in the "open" ends of the segments. To prevent the wood chipping out inside the mortice, a small sacrificial "spelch" block could be inserted for support before each drilling.

Each segment could then be dry fitted, and using the same brad point drill bit used to make the holes as a transfer punch, to mark the position where the holes intersect the tenons.

Next I could now drill the tenons, but moving the hole position about 1/32" closer to the shoulder of the joint. Making up some slightly over length walnut dowels, one end was then taper a bit. To bring the hole joint together, the tenon was glued up and inserted into the mortice. The dowel could then be driven through the holes. The slight mismatch in hole position in the tenon having the effect of pulling the joint very strongly together.

First I glued up two halves of the frame and let that set. That way there was still scope to adjust the fit if required.

An arrangement with some traditional wooden hand screw clamps allowed the rather unwieldy ring to be pinned to the assembly table / table saw. The final draw bore pins could be driven in used a club hammer as a backing block to hammer against.

The resulting segments joints up close:

Mounting the ring

The next job was to produce a pair of bearers to carry the ring and join it to the base. These were half lapped in the middle, morticed to fit the tenons on the top of the base. The final joint here also be done with wooden pins, however these were turned a half mm smaller in diameter to make them an easier slide fit. In this was the table top can be dismounted and moved separately from the base (handy for getting it out of the workshop!)

At this point I decided on a slight design change, to make the final fitting of the top slats easier. That was to cut a slot mortice around the inside of the octagonal perimeter ring. (that would have been easier before all the bits were glued together.

Slats

The tedious bit now started. The top needed lots of 7/16" thick slats about 2" wide. To make these I started with a length of 7"x2" board, and planed both sides parallel. Then ripped thin slats off it on the bandsaw (to waste less wood due to the narrow blade kerf). Each of the individual slats then prepared with the planer thicknesser to get a nice finish and a consistent thickness.

The edge of the slats against the perimeter would need a small rebate made in the top face, which would then leave and offset tenon that would engage with the rebate cut around the inside of the ring. The other end would simply lay flat on, and be glued to the radial cross rails.

Cutting the angled rebate into the top face with the mitre gauge and a dado stack in the table saw:

Offering up the tenon:

The tenons could then be inserted into the table ring. Fitting:

The finished result at that end looked ok, and it was easy to keep the joints nice and tight.

Finished Joint

The far end at the intersection with the cross rail was a little harder to get good tight looking joints on. In the end I could the best way to get a good fit was to dry fit all the joints and one end, leaving the slats a little long.

Tape everything in place, and then cut all the tail ends using a sawboard

A thin shim of pine off the side of a 4"x2" acting as a protection to keep the blade clear of the table

Finally everything could be glued in place, and the tail ends of the slats clamped or weighted into place while the glue sets.

Finishing

Before finishing everything was sanded to 120 grit. And the individual bits were stained with a ronseal medium oak spirit based wood stain. (This as it turns out was a slight error - I was aiming for the slightly lighter tone that I used here, but now I am thinking that might have been a light oak stain rather than medium)

The Base Stained

The final stage was oiling, with Liberon Danish oil. This was applied with at least 4 coats on the all the weather accessible surfaces.

The Top Oiled

One of the last jobs was to make up a square walnut plug to fill the centre gap between the slats. This was cut so the end grain would be visible and run diagonally. The top was set slightly recessed but with a pillowed shape to bring the centre of it up level with the table surface.

The Base Oiled

The oiled finish nicely bringing out the contrast between oak and walnut.

Waxing

Once final job will remain once the finish has had a good few days in the sun to fully harden, and that is to gently de-nib the surface with a very fine abrasive, and apply some paste wax. Once buffed out, this will further protect the wood, but also bring down the shine to a more satin finish.

Completed Table

Revisited

After a few years in the garden, a couple of problems began to show up. The first was expected - that the oil finish would not like being left out in all weathers. The original plan was to make a cover for it in the winter, but that never happened! The scond problem was were the top slats were made from quite thin timber (to keep the weight down), some of them were starting to warp quite badly - creating an uneven table surface.

So the solution was to remove the table top and take it back to the workshop for some TLC.

The warpage problem was addressed by cutting four additional bracing bars to place under the mid span of the slats. These were then glued and screwed to every slat - pulling them all back into line:

As the oil finish had weathered, the oak had also stained black somewhat and lost its shine. So I decided to partially sand it back, and then use a couple of coats of a Sadolin style penetrating undercoat with a film based top coat finish.